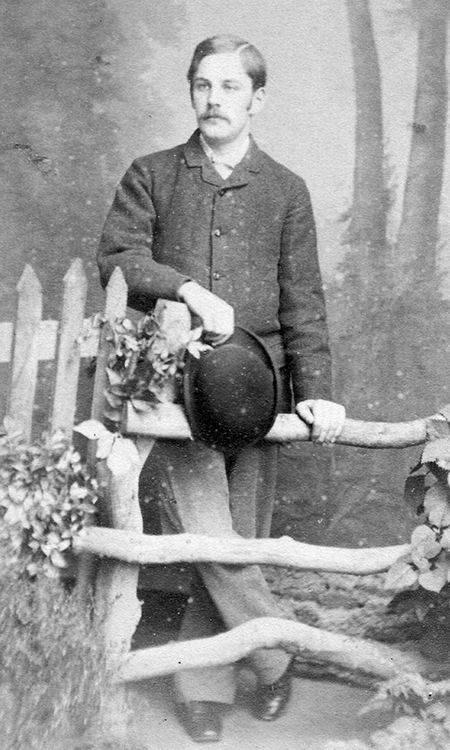

Family collection

TO READ MORE OF ANY SECTION, JUST CLICK ON THE TITLE

Early Life

Lionel was a typical young boy in many respects except for his early exposure to a Victorian doctor's life, which set the idea of becoming a surgeon into his heart at a very young age.

He recounts of his Grandfather, William Weston:

"... he kept a good table, though there was no extravagance. When I stayed with him, a pudding was always served before the meat, which was the custom in those days. Meat was so expensive that they gave you a good feed of pudding first in the hope that you would not want so much meat afterwards."

If we have any doubts of his intention to be a surgeon himself, we find that Lionel was an early starter. His early experience reminds us how primitive conditions were and how much taking fees was tied up with medicine.

"While I was still a child I had made up my mind that I would be a surgeon. My mother often put before me the disadvantages of a surgeon's life, but it was of no avail..... I used to drive with my father on his rounds and later I often rode on a pony beside him. I took every opportunity of visiting the infirmary - and before I was ten years old I often went into the wards. I also got into our own dispensary as often as I could and saw various dressings and extractions of teeth. The first effort I made myself was when i was eleven years old. "

The tooth extraction took place on a local neighbour, a wheelwright.

"I agreed to undertake the operation. I rushed home and secured an old pair of forceps that my father had relegated to the tool basket, and armed with these, I returned. The old man sat on a log in his yard and I extracted the tooth. I failed to obtain any fee, but that did not interest me in those days. When my father found out about this he related the story to many of his friends, with the result that I had several extractions to perform for which I received gratuities."

"My mother was a wonderful woman. She had fifteen children and reared twelve of them. She was always at work for us and made all our clothes: she made my first knickerbockers out of my father's old clothes. It was to help her a little by keeping us out of her way that my father used to take us out with him on his rounds."

Yet another story, from his early years of working with his father shows Lionel's precociousness and gives just a hint of the changing world he was living in. It also says a lot for the patient's willingness to endure pain stoically in a way that seems almost impossible to grasp today:

"Some years later that parlour-maid married the gardener and they took on a small farm..... she had the misfortune to have her hand bitten by a dog......"

After several months, the hand became swollen. Despite several incisions, the infection "got into her upper arm and the limb became gangrenous.I recognised the only way to save her life was to amputate her arm. She repeatedly refused to allow this....

After sitting beside her bedside for two hours Lionel finally persuaded the woman to have the gangrenous arm removed. She had the operation and recovered.A week later, she was able to tell him: "Ah, Sir, I know you have saved my life, but I should never to have agreed to the operation only I suddenly thought of you sitting in your father's carriage when I used to bring you out milk and minced pies."

The interesting comment Lionel added was that the case against the owner of the dog eventually went to court, where Lionel gave evidence. "I gave evidence at the trial and stated that in my opinion the condition was caused by germs that had remained latent in her system until her body vitality was so lowered that they were able to get the upper hand This was a point that at that period had not been advanced, but the possibility is now a generally accepted fact. The judge accepted my opinion and awarded compensation."

Family collection

Education and Apprenticeship

Lionel's interest in surgery and medicine could be said to have started at his father's knee. He took a precocious interest in treating people from a young age, but clearly preferred sport to learning at school. He seems to have had a practical, no-nonsense bent, which may have been why he valued the way he had learnt, especially his apprenticeship, into his old age. Anecdotes from his biography also prove he was a keen student of modern medicine and surgical techniques throughout his life.

"Our early education was chiefly what we picked up rather than any formal instruction... I know on one occasion when my mother was giving us dictation I got into great trouble for spelling Europe Yourup"

But actually Lionel as a young boy showed little interest in education. As he said himself of the ten year old Lionel going to the local Grammar School, "... I had a distaste for lessons and had always evaded them by every means I could think of, so I naturally found myself behind my fellow-pupils of the same age."

He was the sort of student who did only what he had to do to avoid punishment, while at the same time he excelled at all types of sport "I never did any work that I could avoid at school..... It was at games that I excelled. I was captain of the cricket and football teams and the leading spirit in some exciting paper-chases. At the time W G George was at the height of his fame and I ran against him several times."

Lionel left school in 1876 "not having passed any qualifying examination."

Lionel left school with no qualifications.

I was then sent to a coach in Birmingham to be prepared for the preliminary examination of the Royal College of Surgeons........ My coach was a classical scholar, a member of the medical profession and a kind of recluse. He prided himself that no woman had entered study for 15 years. I went there every day by train and used to take books with me, which I studied on the journey there and back I had only a short time for preparation, but I passed the examination in March, 1877 (for the Royal College of Surgeons)

... I was apprenticed to my father, who had an extensive general practice, in 1877. In the light of all my later experience, and in spite of all that has been done to improve the education of medical men, I still consider the old system of apprenticeship was the best. We have nothing to equal it nowadays.... Even now, if I had my time to come over again, I should choose to be ediucated by the same system as was followed in my early medical training, when boys of sixteen or seventeen years of age were apprenticed to general practitioners.

.... Under the system of apprenticeship, by the time a young man had finished his apprenticeship, he was able to open abscesses, extract teeth, perform other minor operations, and use a thermometer and a stethoscope with more or less accuracy. He had an intimate acquaintance with all minor ailments and a more superficial one with serious complaints. He had also learned how to deal with patients, using tact and discrimination.

Lionel believed that doctors should be responsible for making up their own medicines and that it was better of patients had no real idea about what they were being prescribed.

"Moreover, say what you like, the element of mystery is a very large factor in the treatment of disease and therefore it is far better if patients should not know what they are taking."

Lionel went to work with another doctor in January, 1878.

One patient caused me much anxiety. I could not decide what was the matter with him, so I sent for my father to come and see him with me. To my great astonishment, my father said to me as we entered the house: 'Your patient is suffering from rheumatic fever.' 'How do you know that?', I asked. 'I can smell him.' was his reply, and he was right. This gave me a lesson that has been very useful to me many times since."

Lionel visited Berlin in 1890 to learn more about the breakthroughs in the study of tuberculosis that had been made by Robert Koch.

"We watched the injections of tuberculin and our interpreter expained to us the chief remarks of the physicians."

During the stay, they went to different hospitals and Lionel gives the impression of rather approving of the "strict discipline" the patients were under. "This is a great contrast to the methods adopted in our own country. All the bodies were subject to post-mortem examination, and the work was thoroughly well done"

He was to make a second visit to Germany in June 1908, where he became the elected speaker for the medical party."I did not mind in the least, for I was accustomed to, and rather fond of speaking in public..."

Family collection

Training as a Surgeon

It was at St Bartholomew's that Lionel really began to concentrate on his career. From the start of his time there he became a serious student, giving up much of what he had previously enjoyed in order to study. This may also have been due in part to the feeling he had that he should be careful with his money because of the family's financial situation.

Lionel went up to London in October 1878 and made an early decision to choose study over the temptations of the city

"There were so many temptations in London and so many tragedies among the students of the hospital. I can quite conceive that I might have gone altogether wrong if I had been introduced into a fast set."

Even the delights of sport had to be put to one side.

"I was devoted to cricket and football and hitherto hard study had little attraction for me. But in less than twenty-four hours at the hospital, I learnt that if I was to succeed in my profession, work - and very hard work - was necessary..... I therefore packed up my football and cricket things and sent them home at once in order to remove temptation as far as possible."

To begin with, he felt intimidated by the other students and by the work load, but found that his apprenticeship actually gave him some advantages over the other students.

"I felt almost overwhelmed with the task that was before me, especially when I compared myself with other students. There were probably over 700 of them in all, among whom were many university men. However, I set to work in earnest. I attended all the lectures, did a great deal of dissecting and kept regular hours for the reading. The knowledge of chemistry, physiology and anatomy that I had gained during my apprenticeship stood me in good stead when I entered the hospital, for I was able to learn them more easily than if I had been a raw recruit. And when I went into the wards and the outpatients departments, I was immediately placed at an enormous advantage, because I could do all the minor operations we were allowed to do with a degree of knowledge and skill never possessed by the students who had not been apprenticed...."

"In 1880, I went up for the Royal College of Surgeons examination and failed. This seemed surprising, because at St Bartholomew's I had been bracketed first in the physiology examination and I was second in the anatomy examination. The reason for my failure was that I had foolishly misread one of the questions."

Lionel went on to qualify four months later and became a member of the Royal College of Surgeons. He also qualified as an Apothecary. He was appointed a junior anaesthetist at St Bart's giving "up to fifty anesthetics a day".

"In May 1881, I contracted diptheria and scarlet fever and was so ill that both my father and my mother were sent for. In my five days of delirium I went to all sorts of places and did all sorts of peculiar things, which I remembered perfectly afterwards; but I want to put definitely on record that I never suffered in the very slightest degree; in fact I had a jolly good time"

That his parents were seriously worried about Lionel’s life is evidenced by this letter, written by Samuel and published in the BMJ on July 30 1881:

AMBULANCE CONVEYANCES IN LONDON.

Sir,—I am glad to note your article upon Dr. B. Howard's letter, asserting the great need for ambulance conveyances for the sick and wounded in London.

Two months ago, I was summoned to town to find a medical student (my son) in great danger, with diphtheritic throat; and, feeling his life could only be saved by an immediate removal from his lodgings to hospital care, I cast about for a proper conveyance. Various messengers were sent to different owners of the same; at last, one was found willing to undertake the removal, a distance under at mile. He would not show his vehicle, or promise it, before at deposit of ten shillings was made.

On its arrival, I was in dismay; the landlady and the whole square deeply shocked at the sight of the conveyance. I can only describe it as a cross between a hearse and dirty linen cart, painted black, and with funereal side glass; a black horse, with dismal harness, and a driver of the most woeful aspect, also in deep black. It was surely enough to put the finish to any sensitive patient, dangerously ill, as my son then was. Surely, in these days, the metropolis will not long delay this much needed proper ambulance provision.

I am, faithfully yours, Samuel Stretton M.R.C.S.Eng.

Kidderminster, ]uly, 1881

Patients sometimes proved the trickiest thing to cope with.

"I always remember the story of an old lady who lived in one of the streets of the neighbourhood and was famed for her wonderful cough lozenges, of which she sold quantities. It was ultimately found out that the principal ingredient of these lozenges was the 'hospital linctus', for which she used to come regularly."

But if patients might prove tricky, it enhanced the observational skills Lionel needed to become a good doctor.

"The facial expression is one of the most valuable diagnostic signs. An observant and experienced medical man, on walking through the wards of a hospital can tell you how the patients are,and what is the matter with a good many of them, even though he has never seen them before."

by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, early 19th century - reproduced from Wikipedia

Life at 27 Church Street

Although the return to Kidderminster was unexpected, the house at 27, Church street was to become the centre of his life for more than 50 years.

"Suddenly, early in August, 1882, I received a telegram summoning me home, because my father was very ill. I made all my arrangements and came home. The physician in attendace told me that unless I resigned my positions in London and came home to help my father he would not live long. He had a family of seven sons younger than myself to educate, so I had no choice.I immediately went back to London to hand in my resignations of the positions I had been looking forward to holding. I then wrote to my father that I was willing to give up my London career, which I felt to be pretty well assured, and come home to help him in any way I could. I left the terms to him and made only one condition that I must have a house to myself. In making that condition I showed wisdom beyond my years. After completing the arrangements for resigning my posts at St Bartholomew's Hospital I left there on August 9th, 1882, and came to join my father in parthership."

Despite his father's urgings, Lionel never took a holiday but moved straight in to 27 Church St, then set to work.

"I settled down in the house I was to live in for fifty six years..... My income then was very small. My sister came to keep house for me; we had an old man and his wife to look after the house and garden, and a boy acted as 'Buttons', answered the bell and valeted for me.

"My father resigned from the hospital staff and I applied for the vacant position as honorary surgeon. In support of the application, I had many testimonials from the leading physicians and surgeons at St Bartholomew's Hospital........ I obtained the appointment at the hospital and resigned it only at the end of 1938."

"In 1882, as my father's partner, I was appointed Deputy Medical Officer of the Workhouse and District, and Surgeon to the Kidderminster Lying-in Charity; the last-mentioned provided me with upwards of 100 midwifery cases a year."

"My first two years at Kidderminster were very strenuous ones. I did practically all the work at the workhouse and in the parish district, and all our own dispensing and book-keeping. The practice increased to such an extent in these two years that I ultimately gave way to my father's advice that I should have an assistant."

"I was married in April, 1884, having known my wife since childhood"

Lionel was married to Lucy Emma Houghton

"In the year 1904, I had a serious illness which nearly cost me my life. After a heavy day's work, I felt my arm itching in the evening and found there was a malignant pustule on the outer side of my left forearm. There had been a case of anthrax in the hospital and I might have got infected from it. This was before the days of the anti-anthrax serum. Within half an hour of finding the pustule I had it excised under a general anaesthetic. I kept on with work for several days, carrying my arm in a sling. My condition grew worse and when I found my temperature was 103°F, I went to bed. Within forty-eight hours I was delirious, with a temperature of over 105°F. I remained unconscious for five days"

Lionel described being able to remember nothing about the illness, but used it as an anecdote with which to comfort other people subsequently.

"The delirium was different on this occasion, for I cannot remember a single thing from the time when I became unconscious until I woke up again. But I am quite clear that I did not suffer at all and, as previously indicated, it is very satisfactory to me to be able to comfort people by assuring them that delirious patients are not really suffering."

Lionel clearly had a very robust constitution as he was told by the physicians that he should not go back to work for at least six months. He defied all expectations of him:

.... In less than six weeks I went into Nottinghamshire and performed an abdominal operation. The powers of recuperation are very great in some people. No doubt I had lost a stone or two in weight, but as soon as I could I went to Droitwich and had a massage and gentle exercise, and I very soon felt alright again. It is largely a question of nervous energy, grit and determination.

"My father had retired and was living in Droitwich when the fiftieth anniversary of his wedding came round. To celebrate the event he and my mother held a large reception in the Kidderminster Town Hall, where they received many congratulations and handsome gifts. Their children gave them a gold loving-cup, which was handed to them at a luncheon party at my house, where thirty memebers of the family were present."

"Twenty-seven years later, in 1934, my wife and I celebrated our own golden wedding by having a family dinner party at home. We also received many congratulations and beautiful gifts."

Family collection

A Doctor's Life

Over the course of more than 50 years, it is unsurprising that Lionel has many anecdotes to tell about the practice of medicine. He seems to have felt almost uniformly strongly in favour of nursing and the nursing profession, whereas his experience of medical assistants and house surgeons was a little more chequered.

Lionel thought very highly of good matrons and nurses, describing how much could be learned from them if only you were prepared to do so.

"Even when I was a medical student I realised that there was a great deal to be learned from the Sisters and nurses in the hospital wards and I took every advantage of this...... I am very angry with men who do not show them proper respect. It is absurd for a medical student or a doctor to try to make out that he knows everything and the nurses know nothing; there are many occasions when they know better than he does."

Lionel recounts his views on the varying quality of assistants.

"One of the best assistants we ever had was a Scotsman. He was a total abstainer and he did his work excellently, but he had a cast in his one eye, which gave him a peculiar appearance. One does not like to be too inquisitive and stare at people too much, but I had my suspicions about that eye."

The assistant was laid up with influenza and received a visit from Lionel.

"When I knocked at his door I heard him jump out of bed and I was just in time to see him pick something up from the dressing-table and clap it into his eyelids - an artificial eye. This assistant stayed with us until he married and did exceedingly well afterwards."

The practice seems to have been particularly unlucky with assistants who liked a drink or two too many.

"Another Irishman we had was quite a good man for the first five or six months, until he had to attend a patient suffering from delirium tremens; within a few days he was practically in the same condition himself. It is strange that this should have set him off; he had evidently been a drunkard who had reformed. I could tell by the smell of his breath that he had been drinking our tinctures. It would have been dangerous to keep him, so I instantly paid him off and dismissed him."

Another assistant had barely arrived before he had to be dismissed for drinking.

"An Irishman from Dublin applied for the post, stating that he was a total abstainer, and we engaged him. He arrived late on night and as I was unwell I did not see him that night."

The smell on the assistant's breath and his shaking hands were the giveaway. Lionel went to question the man's landlady.

"'Oh, she said, 'he was very drunk when he arrived. He put his feet on the grate and burnt the soles off his new shoes. He had a big dose of brandy before he got up and a pint of beer for his breakfast.'"

Inevitably the man had to be dismissed for the safety of the patients when he had barely begun the job. Lionel found out from the assistant's brother that he had been a compete drunkard. The family had got the man to sign the pledge, got him a new outfit and sent him over to England.

A rather more intimidating case was that of another Irishman "a champion athlete, a great burly fellow over six weeks in height " who got into fights in the local pubs, so that Lionel felt he had to sack the man.

"I was rather frightened by this, however, because a few years before an assistant employed by my father and his partner, when reproved by the latter, knocked him down and blacked his eye. This called forth a paragraph in next week's local newspaper headed 'When doctors differ, they fight to decide.' So I poked my head round the door of the man's room, told him he had to go and sent him his money when he went to have his supper."

In another example, we learn of an assistant who seems to have got the better of his employers, as Lionel rather ruefully observed.

"Another assistant my father has had objected very much to the partner and was always saying what he was going to do to him. His one great idea was to let the pig loose in the garden, and he actually did this the night before he left.. I looked upon him as rather a simpleton. For instance,..... he always had an ample provision of the very best Havana cigars with which he supplied us all freely. We thought it was a pity he should smoke such good cigars, so we bought him some penny ones with which we used to present him He would smoke these penny cigars and dilate upon them, their beauty, the perfect aroma and so on, while we were smoking his Havanas and laughing up our sleeves. But I fancy he had the laugh on his side after all, because after he had left my father and his partner found that the Havana cigars had been ordered from their druggist and put down on their bill, and they had to pay for them. The assistant could not be found."

Lionel thought that practising in a local hospital was better for a surgeon's general experience.

"It is well-known that a House-Surgeon who is keenly interested in his work will probably get greater experience in comparatively small hospital than in a large one, especially if the smaller one does many kinds of work and a great deal of surgery."

Some of them left a lifelong impression with him, not always for the right reason.

The first House-Surgeon I remember at the hospital was there when I was a child. He once went temporarily off his head and had to be taken to an asylum. One day I was sitting in my father's carriage at the door of the hospital and another carriage and pair was waiting to take the House-Surgeon away. He came out of the door, got into my father's carriage and began to sing to me. Nothing would move him out of that carriage.

They had to drive several miles out of town before the man could be persuaded to stop singing and get into the one that was intended for him. Pleasingly "...He recovered completely and did quite well in later life"

Another excellent House-Surgeon, also from one of the leading hospitals, was found by the old matron one night in a very compromising situation with one of the Nurses. Of course, both he and the Nurse were immediately discharged.

Lionel was sympathetic towards the pressures that young doctors faced in their early careers, saying,

"The early part of the medical career is particularly trying to some men, and many of those who fail to make good are more deserving of pity than censure."

Lionel thought that the best surgeons were "born, not made", though training in surgery and medicine could never be too thorough.

"If a man is to attain clinical acumen and diagnostic skill he must have a knowledge of all branches of the profession."

He was dismissive of doctors who were too lazy or too arrogant to learn all aspects of the job as he had done as an apprentice.

"....many of them despised detail and suffered so severely from the condition known as 'swelled head' that it was difficult to teach them.

He felt that just participating in occasional surgery would not be sufficient to allow a surgeon to keep his hand in.

"In order to obtain this (sufficient practice) a surgeon must have thirty or forty beds at his disposal in a properly equipped hospital"

He felt that surgeons should be properly qualified and demonstrate the practical skills necessary before they were allowed to practice. Likewise, General Practitioners should not even undertake the smallest surgical procedure, even though he had done this himself.

"It may seem curious that I should write this, for I developed my own surgery while I was carrying on an extensive general practice..... Like many others I was a victim of circumstances; I was obliged to assist my father in his practice to enable him to bring up his large family." In an interesting postscript to the changing world of medical practice, he concluded by adding that his general practice declined over time as he undertook more and more surgery.

As for what made for a great surgeon, he felt that the essentials were, "general and special knowledge, good health, the power of quick decision and immediate action, thoroughness, the ability to perform rapid and controlled movements without hurry, courage, artistic skill", but that he needed to have the "surgical temperament...... coolness, calmness, collectedness." and a mastery of his emotions to be considered great.

Family collection

Thoughts on the Profession

Over the course of more than 50 years, it is unsurprising that Lionel has many anecdotes to tell about the practice of medicine. He seems to have felt almost uniformly strongly in favour of nursing and the nursing profession, whereas his experience of medical assistants and house surgeons was a little more chequered.

Lionel thought very highly of good matrons and nurses, describing how much could be learned from them if only you were prepared to do so.

"Even when I was a medical student I realised that there was a great deal to be learned from the Sisters and nurses in the hospital wards and I took every advantage of this...... I am very angry with men who do not show them proper respect. It is absurd for a medical student or a doctor to try to make out that he knows everything and the nurses know nothing; there are many occasions when they know better than he does."

Lionel recounts his views on the varying quality of assistants.

"One of the best assistants we ever had was a Scotsman. He was a total abstainer and he did his work excellently, but he had a cast in his one eye, which gave him a peculiar appearance. One does not like to be too inquisitive and stare at people too much, but I had my suspicions about that eye."

The assistant was laid up with influenza and received a visit from Lionel.

"When I knocked at his door I heard him jump out of bed and I was just in time to see him pick something up from the dressing-table and clap it into his eyelids - an artificial eye. This assistant stayed with us until he married and did exceedingly well afterwards."

The practice seems to have been particularly unlucky with assistants who liked a drink or two too many.

"Another Irishman we had was quite a good man for the first five or six months, until he had to attend a patient suffering from delirium tremens; within a few days he was practically in the same condition himself. It is strange that this should have set him off; he had evidently been a drunkard who had reformed. I could tell by the smell of his breath that he had been drinking our tinctures. It would have been dangerous to keep him, so I instantly paid him off and dismissed him."

Another assistant had barely arrived before he had to be dismissed for drinking.

"An Irishman from Dublin applied for the post, stating that he was a total abstainer, and we engaged him. He arrived late on night and as I was unwell I did not see him that night."

The smell on the assistant's breath and his shaking hands were the giveaway. Lionel went to question the man's landlady.

"'Oh, she said, 'he was very drunk when he arrived. He put his feet on the grate and burnt the soles off his new shoes. He had a big dose of brandy before he got up and a pint of beer for his breakfast.'"

Inevitably the man had to be dismissed for the safety of the patients when he had barely begun the job. Lionel found out from the assistant's brother that he had been a compete drunkard. The family had got the man to sign the pledge, got him a new outfit and sent him over to England.

A rather more intimidating case was that of another Irishman "a champion athlete, a great burly fellow over six weeks in height " who got into fights in the local pubs, so that Lionel felt he had to sack the man.

"I was rather frightened by this, however, because a few years before an assistant employed by my father and his partner, when reproved by the latter, knocked him down and blacked his eye. This called forth a paragraph in next week's local newspaper headed 'When doctors differ, they fight to decide.' So I poked my head round the door of the man's room, told him he had to go and sent him his money when he went to have his supper."

In another example, we learn of an assistant who seems to have got the better of his employers, as Lionel rather ruefully observed.

"Another assistant my father has had objected very much to the partner and was always saying what he was going to do to him. His one great idea was to let the pig loose in the garden, and he actually did this the night before he left.. I looked upon him as rather a simpleton. For instance,..... he always had an ample provision of the very best Havana cigars with which he supplied us all freely. We thought it was a pity he should smoke such good cigars, so we bought him some penny ones with which we used to present him He would smoke these penny cigars and dilate upon them, their beauty, the perfect aroma and so on, while we were smoking his Havanas and laughing up our sleeves. But I fancy he had the laugh on his side after all, because after he had left my father and his partner found that the Havana cigars had been ordered from their druggist and put down on their bill, and they had to pay for them. The assistant could not be found."

Lionel thought that practising in a local hospital was better for a surgeon's general experience.

"It is well-known that a House-Surgeon who is keenly interested in his work will probably get greater experience in comparatively small hospital than in a large one, especially if the smaller one does many kinds of work and a great deal of surgery."

Some of them left a lifelong impression with him, not always for the right reason.

The first House-Surgeon I remember at the hospital was there when I was a child. He once went temporarily off his head and had to be taken to an asylum. One day I was sitting in my father's carriage at the door of the hospital and another carriage and pair was waiting to take the House-Surgeon away. He came out of the door, got into my father's carriage and began to sing to me. Nothing would move him out of that carriage.

They had to drive several miles out of town before the man could be persuaded to stop singing and get into the one that was intended for him. Pleasingly "...He recovered completely and did quite well in later life"

Another excellent House-Surgeon, also from one of the leading hospitals, was found by the old matron one night in a very compromising situation with one of the Nurses. Of course, both he and the Nurse were immediately discharged.

Lionel was sympathetic towards the pressures that young doctors faced in their early careers, saying,

"The early part of the medical career is particularly trying to some men, and many of those who fail to make good are more deserving of pity than censure."

Lionel thought that the best surgeons were "born, not made", though training in surgery and medicine could never be too thorough.

"If a man is to attain clinical acumen and diagnostic skill he must have a knowledge of all branches of the profession."

He was dismissive of doctors who were too lazy or too arrogant to learn all aspects of the job as he had done as an apprentice.

"....many of them despised detail and suffered so severely from the condition known as 'swelled head' that it was difficult to teach them.

He felt that just participating in occasional surgery would not be sufficient to allow a surgeon to keep his hand in.

"In order to obtain this (sufficient practice) a surgeon must have thirty or forty beds at his disposal in a properly equipped hospital"

He felt that surgeons should be properly qualified and demonstrate the practical skills necessary before they were allowed to practice. Likewise, General Practitioners should not even undertake the smallest surgical procedure, even though he had done this himself.

"It may seem curious that I should write this, for I developed my own surgery while I was carrying on an extensive general practice..... Like many others I was a victim of circumstances; I was obliged to assist my father in his practice to enable him to bring up his large family." In an interesting postscript to the changing world of medical practice, he concluded by adding that his general practice declined over time as he undertook more and more surgery.

As for what made for a great surgeon, he felt that the essentials were, "general and special knowledge, good health, the power of quick decision and immediate action, thoroughness, the ability to perform rapid and controlled movements without hurry, courage, artistic skill", but that he needed to have the "surgical temperament...... coolness, calmness, collectedness." and a mastery of his emotions to be considered great.

Family collection

Thoughts on Life

We get a much clearer idea of Lionel the man from his thoughts on life, where his views covered everything from holidays to hats.

"In the question of holidays, as in regard to other questions, individuals vary. Some men - and I am happy to be one of them - are so infatuated, may I say, with their occupation that they never want to leave it and they do not get stale at it. I think this applies more particularly to a profession like my own, which holds so much variety...... No two cases are alike and the study of their infinite variety is so fascinating to me that I have been unable to tear myself away for the past thirty years. I cannot help feeling that my own experience negatives the present-day fetish that an annual holiday is necessary for everybody.... I quite admit that an annual holiday is agreeable to most people, but that is a very different thing from being necessary. When it is said to be necessary, presumably it is from a health point of view."

As for children, he considered holidays for them unnecessary, saying, "I hold the view that not only are holidays unnecessary for them but that children in most instances are better at home. Parents would derive more benefit from their holidays if they left their children at home..... I would take children for holidays only when they are old enough to appreciate it, and as part of their education."

Despite his comments, Lionel travelled extensively including a month long appointment with a lady which involved travelling all over Europe in 1889 as part of her medical treatment. On his return to England, it was the food he was happiest to get back to.

"I was very glad to get back to London and the good old English custom of a cut from the joint. The foreign food was all done up in a tasty fashion, but I never knew what I was eating."

Even if his attitude to holidays was slightly ambivalent, Lionel clearly enjoyed exercise, walking, cycling and golf. His cycling tours took him all over the United Kingdom. "All parts of our islands have their own particular beauty and are well worth visiting, and in most of the towns there is excellent accommodation."

"If you want to know a country there are few better ways of doing it than by making tours on a push bicycle."

It was, he said a much better way of seeing the countryside: "Having travelled a good deal by both, I unhesitatingly assert that the motor vehicles convey you through the scenery far too quickly to enjoy its beauties; on the push-bicycle you can quietly meander along and when you come to any specially attractive spot you can get off your bicycle, sit down and give yourself time to observe and enjoy it thoroughly."

Like many Victorians, Lionel valued thrift highly, preaching the value of saving from an early age. This appears to have come from his father's financial position. "... and my own reason forced me to believe they were in financial difficulties, with a large and increasing family to bring up and educate. My affection for them was so profound that I felt it my duty to deny myself in every possible way in order to make things easier for them."

Lionel saw the way he dressed and behaved an essential part of what it was that defined him professionally.

"Far from being ashamed of being Victorian, or early Victorian, I am rather inclined to glory in it."

He went on to add, "I was brought up and entered upon my practice when frock-coats and top hats were considered almost the hall-mark of professional men."

"Through all the years of my professional life I have remained faithful to my top hat. For more than fifty-five years my top hat was always deposited in a special place by itself in the hall at the hospital, and it was recognised that if anyone wanted to know whether I was in the building or not, all that was necessary was to go and see if my hat was in its usual place."

He admitted that some amusing incidents had been created as a result of his predeliction for wearing it.

"In the early days of my practice one of my brothers dared me to ride, wearing my top hat and frock coat through the town and up the hill to the hospital on a high bicycle, the so-called penny-farthing. I did it and a most ridiculous object I must have appeared!"

On other occasions he admitted to absentmindedly going out for a night visit in his bright scarlet dressing gown as the patient was seriously ill and only a short walk away. Out of habit, he picked up his top hat from its place in the hall, not realising how he must have appeared until it was time to go back home from the visit.

"I did not realise what a ludicrous appearance I must have presented until I found the hat in my patient's hall when I was leaving his house. However, I put it on and walked home in it."

The hat was such a part of his identity that some people did not recognise him without it.

"One evening I was attending a public dinner as the guest of a doctor who lived in the neighbourhood. He was late and I spent the time of waiting in conversation with a man I knew quite well. When the doctor arrived, he apologised for being late and said to the man with whom I had been talking, 'You know Mr Stretton, of course.' 'Oh yes, I know him quite well,' was the reply, 'but is he here tonight?' I then chimed in: 'Yes, I am here all right.' 'But,' he said, 'you are not Mr Lionel Stretton that's the one I know.' 'Well, I happen to be Mr Lionel Stretton,' Whereupon he answered, 'Then I must apologise, but I have never seen you before without your top hat.'"

Family collection

Serving the Community

As if he did not have enough to do as a busy doctor and surgeon, Lionel was heavily involved in serving the community, in hosptial organisation and administration, in fund raising and in the Chairmanship of various local medical committees.

Of all the bodies that Lionel was connected with, the Kidderminster Hospital has to be the most important

"A man could hardly spend fifty-six years in the continuous service of the same institution...... without acquiring an intimate knowledge of that institution and a feeling that it is a part of himself."

He relates how the hospital grew, first under his father and then under his own leadership. He was especially proud of the nursing training it provided:

"About 1895 the Hospital began a system of training nurses and in 1922 it was approved by the General Nursing Council for England and Wales as a First Class Training School for Nurses"

For Lionel, the highlights were "the period of the war and the opening of extensions by His Royal Highness the Duke of York in 1926"

In 1910, Lionel was invited to be chairman of the Worcester Division of the BMA, having previously been "fully occupied with my practice". Unusually his appointment was extended to a second year because of the introduction of the National Health Insurance Act It was one of the rules of the Association that no member should hold the position of Chairman for two years in succession, but this Rule was suspended to enable me to go on with the regulations relating to the Insurance Act.

He was to alternate as Chairman for Worcester and for the Division of Hereford and Worcester for many years to follow.

During the Great War, Lionel was Chairman of the County committee which decided "...which of the doctors should join up when extra calls were made for the services of medical men in the county."

He conceded that the choices that had to be made were extremely difficult.

"I always explained to any of them.... the Committee could not give any weight to personal reasons.... The one and only point we had to consider was which man could be spared, so as to afford the least possibility of depriving the general public of the efficient medical service they had a right to expect."

Lionel took particular satisfaction from his Chairmanship of the County of Worcester Local Medical and Panel Committee, which he held from 1912

He was also a founder-member of the Kidderminster Medical Society, "In 1893 the Kidderminster Medical Society was formed, with my father as its first President and myself as its first Secretary.... it tends to improve the character of the work of the profession in the district."

Much of Lionel's work involved him in raising funds for the local hospital and local charities. He notes that this was not always well-received:

"When I was collecting the money for a new operating theatre at the hospital I was told that it was said that I was asking for subscriptions to a new slaughterhouse!"

Family collection